As I was exploring Thomas Jefferson’s amazing home at Monticello earlier this month, I thought about the children he had with Sally Hemings. One of them – Eston - and his family are buried at Forest Hills cemetery in Madison. Therein lies a fascinating story.Sally Hemings was the enslaved woman who was essentially Jefferson’s mistress for almost four decades – from her time with him in Paris when she went there in 1787 as a 14-year-old to care for his younger daughter until his death in 1826. When they came back to the U.S. from Paris in 1789, she was pregnant – and she had negotiated with Jefferson that he would free any children they had once they reached the age of 21 or upon his death.

Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson had seven children, four of whom survived. Jefferson with his wife, Martha, also had six children, two of whom survived to adulthood. It was one of them who Sally accompanied to Paris. Martha died in 1782 – and was Sally’s half-sister – same white father, different mothers. The two were said to have a striking resemblance.

The youngest of their children was named Eston – named after Thomas Eston Randolph, a favorite Jefferson cousin. He was born at Monticello on May 21, 1808, near the end of Jefferson’s second term as president.

|

| A replica of John and Pricilla Hemming's cabin |

Historian Annette Gordon-Reed wrote that of the four children, Eston seemed to identify the most with Jefferson. “a near copy of Jefferson facially and physically in terms of height and build.” Music was the passion of Eston’s soul, much as it was for Jefferson. He learned to play the piano and violin and later made his living as a musician. One of Jefferson’s favorite songs was “Money Musk”. (You can hear it on YouTube.) As an adult, Eston made that one of his signature tunes when he played for dances while he lived in Ohio.

When Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, Eston – who was then 19 - and his older brother Madison were freed. (The two older children, Beverly - a man’s name at that time - and Harriet, had been freed earlier when they turned 21 and in time moved to the Washington D.C. area.) When Sally left Monticello in 1826, she lived with Madison and Eston in nearby Charlottesville, later moving in with Madison and his family.

In 1832, Eston married an 18-year old free woman of color, Julia Ann Isaacs. She was the daughter of the successful Jewish merchant, David Isaacs, from Germany, and Nancy West, a free woman of mixed race. Eston and Julia's first child, John, was born in 1835 and their second, Anna, was born in 1837, both in Charlottesville.

Sally died in 1835. Eston and Madison and their families in 1837 moved to Chillicothe, Ohio, to live in a free state. The third child of Eston and Julia - Beverly Frederick – was born there in 1839. As their children grew, they were educated in integrated schools.

|

| The house Eston built in Chillicothe |

People in Ohio seemed to understand that he was a child of Thomas Jefferson and commented on the resemblance when they saw pictures or statues of Jefferson.

|

| An artist's imagined image of Eston |

He was “of a light bronze color, a little over six feet tall, well proportioned, very erect and dignified; his nearly straight hair showed a tint of auburn, and his face, indistinct suggestion of freckles. Quiet, unobtrusive, polite and decidedly intelligent, he was soon very well and favorably known to all classes of our citizens, for his personal appearance and gentlemanly manners attracted everybody's attention to him.”

But people there understood that his mother was of mixed race, as was his wife. That was a social gulf they could not cross. Also, after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, Eston no longer felt it was safe to remain in southern Ohio, and so in 1852 he moved with his wife and three teen-aged children to Wisconsin.

They all changed their last name to Jefferson and were light-skinned enough to identify as white. (Sally Hemings was three-quarters white. Her children with Thomas Jefferson were seven-eighths European in ancestry.)

Eston only lived for four years after coming to Madison. He was said he be demand as a cabinet maker, drawing on one of the skills he had learned from his uncle, John, and had perfected over the years.

But he died on Jan. 3,1856 at the age of 47 and is buried at Forest Hill Cemetery. (This new gravestone incorporates the original. It was put up in the early 2020s by a local group with the permission of Eston's descendants, according to an official at Forest Hill.

Their children were ages 20, 18 and 16 when Eston died.

Anna died about a decade after Eston, on April 11, 1866, at the age of 29 in the Town of Burke just outside Madison. She had married Albert T. Pearson, a carpenter who was a captain during the Civil War. They had three children and one of them - Walter Beverly Pearson - became a wealthy industrialist in Chicago, becoming president of the president of the Standard Screw Company.

|

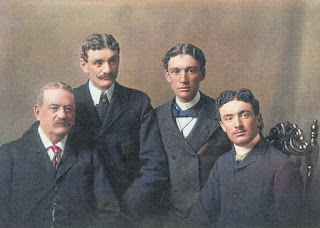

| Beverly and John outside a hotel they managed. |

In 1861, at the age of 26, John Jefferson enlisted in the Union Army and served in the 8th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. He rose quickly in the ranks, named major one month after enlisting, promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1863, and then to colonel in 1864. He was wounded twice – once during the Siege of Corinth in Mississippi in 1862 and then at the battle of Vicksburg, also in Mississippi, in 1863. He was promoted to commander of the entire 8th Wisconsin in 1864 and mustered out of service later that same year.

John Jefferson never married. He died on June 12, 1892, at the age of 57 and is buried at Forest Hill Cemetery.

Eston and Julia’s youngest son, Beverly Frederick, played the biggest role in Madison after the Civil War. Like his older brother, he also served as a solider in the Union Army during the war, part of Company E, 1st Wisconsin Infantry.

When he came back to Madison, he built on what he had learned about the hotel business a bit from brother John before the war. In 1864, he also married Anna Maud Smith, who was born in Pennsylvania in 1846.

Beverly became the proprietor of the Capital Hotel (also known as the Vilas House), located on the eastern corner of Main Street and what is now Martin Luther King Blvd. (formerly Monona Avenue) where there is now a Starbucks.

Historians described it as one of the finest hotels in the state. His obituary in 1908 described him as a “pioneer boniface” –a term for a jovial innkeeper.

|

| Jefferson Transfer Company |

In 1872, Beverly shifted to running the Jefferson Transfer Company - what became the leading firm in the city for using horse-drawn carriages to carry multiple passengers along a fixed route for a fare. Think of it as a precursor to Madison Metro.

He was a member of Masons, GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) and the Old Settlers Club.

Anna died on died Feb. 5, 1882. They had five sons, one of whom apparently died in childhood.

Some time after Anna’s death, Beverly moved into the Park Hotel on the Square and lived there for about 25 years before moving to his son Fred’s home in Chicago, where he died on Nov. 11, 1908 at age 69.

|

| Beverly with three of his sons around 1900. |

But all those political leaders never knew of his connection to the third president of the United States.

The legacy of the Hemings/Jefferson family in Madison is only vaguely known. People are surprised to learn that a son of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson is buried here.

And the story of their family is even less well known, even though their graves are all at Forest Hill.

This family has touched Madison history in so many ways.

Further resources:

The Hemings of Monticello by Annette Gordon-Reed

Getting Word: African American Oral History Project – This project preserves the histories of Monticello’s enslaved families and their descendants. It is an initiative of the International Center for Jefferson Studies. This link is to the page on Eston Hemings.

Julia Jefferson Westerinen, great-great-great granddaughter of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson speaks on several videos about what she has learned. Her line of succession from Eston is through son Beverly, then his son Carl, then his son William, who was her father.

Family Search family trees for Eston and family